I’m 70 years old now. Every morning, I load up an old, second-hand cart with my wooden easel, a couple of blank canvases, and a set of oil paints I’ve been stretching thin for months. Then I slowly make my way five blocks to the same park I’ve been painting in since everything changed.

I set up near the pond, beside a crooked bench with peeling green paint, where ducks gather and kids toss breadcrumbs while their parents stare at their phones. This park is my studio. It’s my world now.

I wasn’t always a painter. For thirty years, I was an electrician, climbing ladders, fixing breakers, untangling wires, and handling difficult customers. I built a good life with my wife, Marlene, in a modest house with a little vegetable garden out back and wind chimes she insisted on hanging from the porch.

I used to laugh at those chimes when they got tangled in storms. I didn’t know it then, but I would miss that sound more than anything when she was gone. Marlene passed away six years ago—lung cancer, even though she never smoked a day in her life. Just one of life’s cruel twists. I thought losing her would be the hardest thing I’d ever face.

Then, three years ago, our daughter Emily, who was 33 at the time, was hit by a drunk driver. She was walking home from the grocery store when a man ran a red light. He hit her full on. Her spine shattered. Both legs broken. Internal injuries. She survived. Somehow. But she hasn’t walked since.

The insurance covered what it could, but the kind of rehab that could really help—specialized neurotherapy, robotic gait training, the whole package—was far beyond what we could afford. Most of what I had went into her surgeries.

What was left went to moving her in with me. We managed to save a little, not much, just enough for a rainy day. She needed full-time care, and I needed something to keep me going.

I didn’t pick up a paintbrush thinking it would save us. I picked it up because I didn’t know what else to do. One night, after Emily went to sleep, I sat at the kitchen table with a sheet of printer paper and an old oil set we found in a box of her childhood things.

I started sketching a barn I remembered from a trip to Iowa when she was seven. It wasn’t perfect, but I’d painted as a teenager, and I just needed to shake off the rust.

Soon, I began watching painting tutorials online, mostly about oils. They felt heavy, grounded, real. Every night while Emily slept, I painted. Eventually, I got brave enough to bring a few canvases to the park.

I painted what I remembered—old country roads, school buses splashing through puddles, cornfields in morning fog, rusty mailboxes leaning in the wind. Places that make you ache for something you’re not sure you’ve ever had.

People would stop and smile. “That looks just like my granddad’s place,” one would say. Another: “That diner used to be down the street from me.” Sometimes they bought a painting. Sometimes they didn’t. Either way, I said, “Thank you for stopping.” Those tiny connections kept me upright.

Last winter nearly broke me. The cold was brutal. I tried to stay warm, but I couldn’t afford to stop. My hands cramped, fingers stiffened, paint froze on the brushes. Some days I made twenty dollars. Other days, nothing. I’d pack up early, walk home with aching knees and numb fingers, and stare at the bills piling up on the counter. Then I’d look at Emily. Her face would soften.

“Dad,” she’d say, “someone’s going to see what you’re doing. They’ll feel it.”

I’d pretend to believe her. She always knew when I was faking it. But she let me keep trying anyway.

One of the worst parts of getting old isn’t the pain—it’s feeling like you’ve already given everything, and the world is slowly forgetting you were ever strong, capable, sharp. That’s how I felt, watching my daughter slowly sink while I had nothing but a leaky bucket to bail water with.

Then, one day, everything changed.

It was a cool early-fall afternoon. I was painting a scene I’d noticed earlier that week—two kids tossing bread to ducks, a jogger running past in the background. I was halfway through when I heard a soft whimper.

I looked up. A little girl, maybe five, stood by the paved path. Pink jacket, two lopsided braids, a stuffed bunny clutched to her chest. Tears streaked her cheeks.

“Hey there,” I said gently. “You alright, sweetheart?”

She nodded, then shook her head. “I… I can’t find my teacher.”

“Were you with a school group?”

She nodded again, sobbing harder.

“Come sit,” I said, patting the bench beside me. “We’ll figure it out.”

She was shivering, so I wrapped my coat around her. She smelled of peanut butter and crayons. I told her a story I used to tell Emily—a brave princess following the sunset colors to find her way home. By the end, she was giggling through tears, still clutching her bunny like a lifeline.

I called the police and gave them my location. Fifteen minutes later, a man in a dark suit came running from the path, tie flapping.

“Lila!” he shouted.

“Daddy!” she squealed, running into his arms.

He held her tight, and I could hear the relief in his voice. After a long hug, he turned to me.

“You found her?” he asked.

“She found me,” I said, smiling.

“Thank you,” he said, blinking. “I was going crazy. Her teacher called thirty minutes ago, and I came running.”

“No need,” I said. “Just make sure she knows she’s loved.”

He crouched and said, “Sweetheart, you scared me. What did I tell you about running away?”

“I… I wanted to see the ducks,” she whispered.

He kissed her forehead, then handed me a business card. “Jonathan. If you ever need anything…”

I tucked it in my pocket and watched them leave.

The next morning, just after breakfast, I heard a loud honk. Outside, a pink limousine gleamed.

“Emily,” I said, squinting, “did you invite Cinderella over for brunch?”

A man in a dark suit stepped up. “Mr. Miller?”

“That’s me.”

“You’re not painting in the park today.”

“Excuse me?”

“Pack up your paintings. You’re coming with me.”

I’m 70, suspicious by nature, but something about him made me trust him. I loaded my cart and followed him to the limo. Inside, sitting like a little queen, was Lila.

“Hi, Mr. Tom!” she beamed, bunny in lap.

Jonathan looked polished, but softer somehow. “I wanted to thank you properly,” he said.

I insisted I didn’t need thanks. But he opened a briefcase and handed me an envelope. I opened it. Inside was a check—enough to cover every cent of Emily’s rehab. Not a few sessions—all of it. And some left for savings.

“Sir… I can’t take this,” I stammered.

“Yes, you can,” he said. “And you will. This isn’t charity. It’s payment.”

“For what?” I asked.

“For your paintings,” he said. “I’m opening a community center downtown, and I want your art on every wall. Your paintings are special. Thousands of people should see them.”

Lila leaned on my arm. “Daddy says you paint love.”

I nodded. I cried. I thanked him over and over.

We packed all the park paintings. When we returned home, Emily watched me load more into the car.

“What happened?” she asked wide-eyed.

“A miracle, honey. A real one,” I said.

Six months later, Emily finished therapy. Despite setbacks, she stood, then stepped, then walked short distances with a walker. Each time, I felt like I’d been given more time with my daughter.

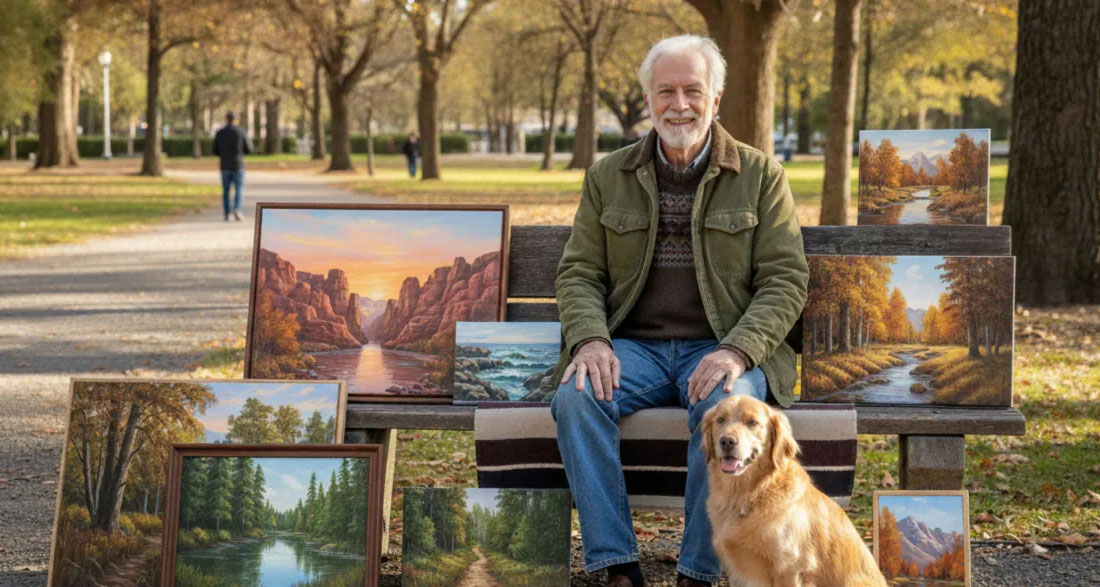

I still paint, every day. But now I have a real studio, a salary, no more worrying about groceries. On weekends, I still set up at that crooked park bench, just to remember where it all started.

When people stop and say, “That looks like home,” I smile. “Maybe it is,” I tell them.

I kept one painting for myself—a little girl in a pink jacket, holding a stuffed bunny, standing by the pond with ducks. That day didn’t just change Emily’s life. It changed mine, too.